Texts for paintings Andrea Pilarová – Belotsvetová

( most of the texts are from the book Bělocvětov – Music of Absolute )

1951 Forest Queen

1951 A child with a floury phantom

1952 Lovers in the Mountains

1952-1953 Portrait of Sudek

1955 Children

1956 Madonna with a pitcher

1958 Dancerine (based on Stanislava Belotsvetová’s poem “Dancerine”>)

1958 Prague Night Tram

1959 Still Life with a Virgin

1959 Still Life with Photographer

1960s, Woman and Child

1960s, Woman with Child II.version

1970s Lovers (reflection on Stanislava B.’s poem “Things Are Happening”)

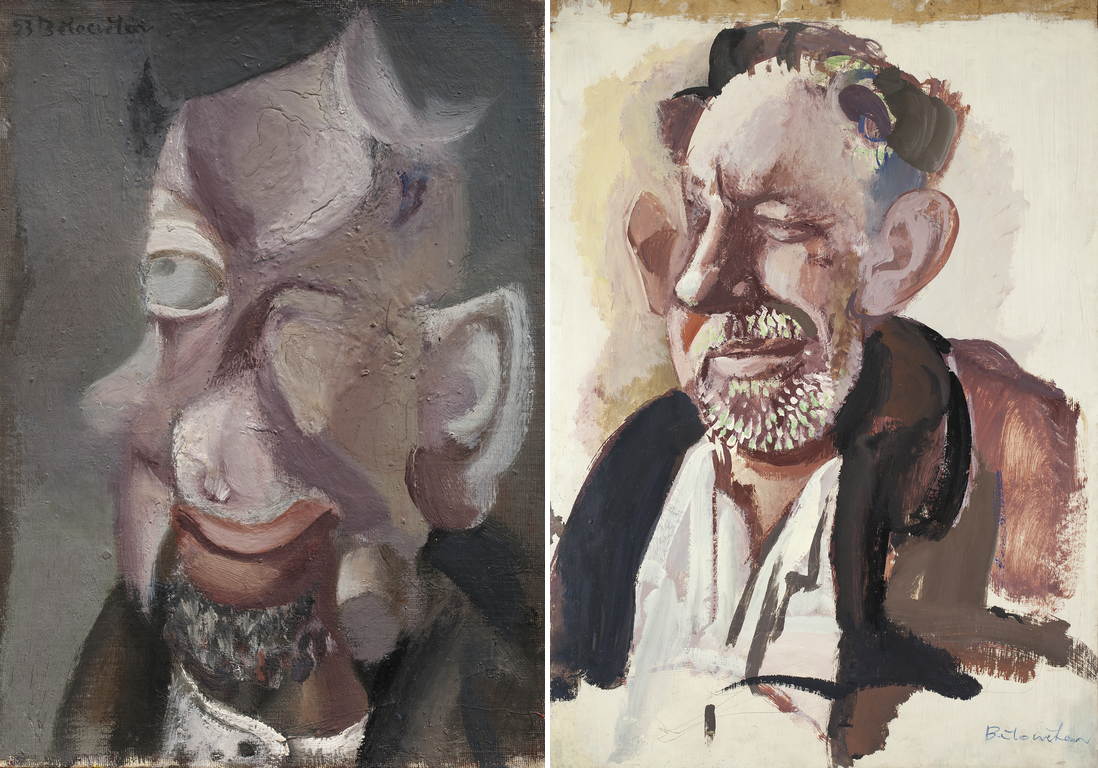

1953 Portrait of Sudek & Sudek 70s

1981 Portrait of Gradiva

1982 Child with a teapot

1989 Sisyphus

1992 Departure

1991 We Are

The Forest Queen

1951, Technique: oil on canvas, size: 115 × 95 cm

The portrait of Stanislava from this period refers to the theme of the Forest Lovers not only by its surreal symbolism, but also by its title, inscribed by the artist directly into the painting: ‘Slavush, between memories of childhood summers, and ambitions for the Forest Queen’. Andrei Belotsvetov was an excellent portraitist who never settled for a superficial depiction of the model’s physiognomy. However, in “The Forest Queen”, as in “The Portrait of Mr. S.”, he achieved such a quite extraordinary insight into the psyche of the model, which he achieved only in a few instances in his outstanding portrait work.

He painted the beautiful face of a woman, but he did not only depict the physical beauty, but also, to an even greater extent and with a considerable amount of suggestiveness, captured her spiritual side. From her dark, melancholy eyes, she radiates an extraordinary being, endowed with deep feeling and such power of thought that she will not allow one to look away. She arouses the desire to witness how the artist, one by one, unveils the veils that cover her interior.

And yet, the last of them – the one that hides the most secret depth of her soul – will never be revealed by anyone.

This mysterious and introverted part of the personality of his otherwise frank and open wife did not seem to leave Andrei in peace. Years later, when they were no longer living together, he draws a nude of Stanislava, kneeling on the ground, about to reveal her eternal secret… (A.P-B.)

A child with a floury phantom

1951, egg tempera on canvas, 130 × 96 cm

Child’s World. We all inhabited it, we were all, to a greater or lesser degree, dazzled by the “spherical explosion” and the music of the absolute. The longing that most people feel for the period of childhood is actually a longing and a yearning for this dazzle. Nothing of the pleasures of the adult world can ever replace it.

Nothing? And yet something: art. I think of when the moment of return to the music of the absolute comes for the creative person, for the artist. It is when he ceases to be subject to the strict and unforgiving rules of craft and technique and instead becomes their sovereign ruler. What was a gift in childhood is now the fruit of long labour, the fruit of a lifetime’s desire.

The painting “The Child with the Phantom of the Flies”, which is one of the most important paintings of the artist’s Neo-Classical period, is not only one of many examples of this “reclaiming”, but is also almost a kind of symbol of it in its content.

The massive yet childlike figure of the child in the foreground is both the inhabitant and the guide of a world full of personified objects, a world seemingly rigidly immobile, beneath the surface of which unbridled life flourishes.

It is enough to look away for a moment and the things – the creatures – start to move and dance a short whimsical dance – a riddle.

The flour-bowl, transformed into a knight’s helmet and immersed in a shimmering silk ornament of white drapery, fixes us with a significant gaze, On its surface runs a flour-worm-phantom with its feathered trident, and the silent melody it utters with its movement can be heard. From the cloth suspended above the bowl, a muscular male arm protrudes: what is it supporting, perhaps a celestial dome?

Behind the child’s hair, drowned in shadows, a long curtain weaves, the folds of which are held by a small insectile creature in the shape of a tree or flower, metamorphosing into a mysterious figure.

Nothing is definitive, everything changes, but these changes are subject to the order of the spherical music that surrounds the whole scene with its constant presence.

The painting “Child with a Phantom”, like other works by the artist, is proof. Proof that when he spoke of his duty to the people, it was not mere words. With an honesty peculiar to himself, he communicated to us the light of not a few, but many loopholes. (A.P-B.)

Lovers in the Mountains

1952, technique: egg tempera on canvas, size: 66,5 × 47 cm

The year-long stay in the Giant Mountains, where the young couple went with their young daughter, had a beneficial effect on the health of the whole family – but it was also highly inspirational for Bellocvet’s work. The atmosphere of the mountain landscape with its deep forests, dark ravines and sunlit meadows forms a meaningful framework for many of the surrealist canvases, perhaps the most significant of which is the painting “Lovers in the Mountains”, full of intimate family symbols.

Later in his life, the painter returned to the theme of the Forest Lovers in cycles and created a large number of paintings and drawings based on it.

They are inspired by the ancient Greek story of the shepherd lovers Daphnis and Chloé, whose young love, despite the powerful trappings of fate, comes to a happy fulfilment in the idyllic setting of pastures and forests. (A.P-B.)

Love Lovers

1952-1953 Portrait of Mr. S.

1952-1953, Portrait of Mr. S., 1952-1953, egg tempera on canvas, 130 × 89 cm

Portrait of Mr. S.

Josef Sudek was an outwardly very folksy, open and humorous man.

Here, however, we see someone quite different; the absolutely accurately characterized, somewhat deformed outline of his figure is in its rigid immobility wrapped in rich drapery, draped with austere grace and majestic grandiosity. In this Renaissance-composed portrait he is depicted as a proud and spirited aristocrat. And indeed he was! A painter friend painted the most intimate portrait of his soul.

Face

A thoughtful, stern face, to which the painter’s empathy and imagination had imbued a deep psychological subtext.

It has two completely different halves. From our point of view, the left side – a mephistophelean pointed ear, matched by the sharp line of a sarcastically raised eyebrow and a dark shadow at the temple. Even the corner of the mouth is lifted – an ironically knowing half-smile. The devilish twinkle of a world-wise and learned observer of human comedy wavers in the piercing eye.

The other half, then, is quintessentially human: the wistful and understanding face of a good man and reliable friend. Belotsvetov knew both his faces, capturing both at the same time, without in any way harming the portrait as a whole. He skated on very thin ice here, but the result speaks for itself.

Hruška

If we are to continue the allusion to the Renaissance portrait, then the pear, standing in the lower right corner and following the line of the coat with striking precision, would function as an attribute of the sitter.

In conjunction with the mysteriously dark outline of the cloth in a straight line above, it is indeed a significant symbol. With its meticulous attention to detail and strange dreamlike charm, it evokes the delicate poetry of Sudek’s still lifes.

The mysterious, floating drapery is none other than the large sail that Sudek used in his work – photographing on glass plates. I can still see the typical movement of his single hand as he inserted the plate and then covered the tripod and his head and shoulders with the tarp.

It was a fascinating and mysterious ceremony, just as painting a picture is.

Josef Sudek persisted in this not only laborious but also physically demanding technique of plate photography because of its specific, irreplaceable characteristics.

Technique

The picture was made shortly after an equally important work by the same artist – The Child with a Phantom.

Both paintings are distinguished by their precisely constructed composition and old-masterly fineness of detail. Together with the sophisticated colouring and the Raphael-like, pearlescent, luminous modelling of the light surfaces, they create an almost musical harmony. This is despite the apparent stillness, which in turn enhances the inner drama of the work. However, while the composition of the painting of the Child is precisely harmonically balanced, in the portrait of Mr. S. we see a deliberate disharmony, which can be compared in a musical parallel to atonal music, while like it it contains its own harmonic field.

It is created by deliberately oversizing the right side of the painting, which, following the ambiguity of the face, further intensifies the psychological characterisation of the portrait.

Using the technique of egg tempera, whose possibilities he was able to make full use of, and with the use of elements of surrealism and mystical realism, the artist completes the metamorphosis of the ordinary into the extraordinary and reveals the spiritual essence of things and events. (A.P-B.)

Children

1955, technic: egg tempera, canvas, size: 115,5 × 80cm

The work dates to the 1950s , the neoclassical period of the artist. Already in this phase of that period, as well as in the later cycle of anticising female figures, a complex and supremely poetic inner dialogue takes place underneath the robustly stylised composition, which here evokes a specifically childlike world. At the same time, the larger of the children symbolizes the coming world of adulthood with his deeply thoughtful , visionary, wistful gaze that looks far into an uncertain future. (A.P-B.)

The anatomy of the child figures – which is the most complex in painterly terms – is handled with bravura ease, both in the sculpted whole and in the fine, almost old-worldly detail.

This is a major work of this artist’s painterly perfection of composition and profound psychology.

Madonna with a pitcher

1956, egg tempera on canvas, 130 × 90 cm

The sculpturally robust handwriting of the painting, typical of this period of the painter, is produced by the silvery Boticellian light flooding the figure of the mother and her child, in an attitude full of intimacy.

The harmony of their joint contemplation rises in gentle musical unison, vertical by vertical, and culminates in a kissed chord of drapery, floating behind the mother’s head and continuing upwards beyond the frame of the painting.

Two pairs of limpid eyes gaze pensively into the space of a mysterious inner world. The little girl, with a boyishly bold face and a stiff helmet of childish hair, dressed in a red shepherd’s cassock, leans with boundless confidence on her mother’s hand, protruding on a golden cut far in front of the surface of the canvas. The mother’s slender figure, full of hidden strength and yet femininely endearing, with her slightly wavy curls and the gently sensuous curve of her lips, stands protectively by her child’s side.

A pitcher, set on a cabinet in the upper corner, completes the leftward composition. The antique simplicity of the pitcher, with the implied clarity of the water, enhances the purity of the scene, combining earthly and spiritual principles into one.

The finest sensations are evoked – the radiant glow of the skin, the exquisitely sculptured forms, and the impression of contrast between the space coming from afar, revealed in the vista between the mother’s head and the drapery, and the confinement of the lower plan, where the figures seem to be pushed out by the heavy outlines of the plain furniture, so that they emerge from the picture with quite extraordinary suggestiveness.

Here the painter has created, on the basis of the neo-classical form and with the use of surreal symbolism, a deeply psychological and subtly poetic work of special charm, offering the viewer one of his many original takes on this immortal subject. (A.P-B.)

Dancerine

1958, (After a poem by Stanislava Belotsvetová) oil on cardboard, 49,5 × 70 cm

Dance

Between two fingers

I’ll spin you skillfully

On the tip of the needle

I’ll build a lock

In the blue room

For the green grasshopper

? to play for you ?

to play

glass march.

So you dance

powered by the wind

Still unchanged

Still built

Of good wax.

Prague Night Tram

1958, oil on canvas, 60 × 70 cm

Prague Night Tram

Andrei Belotsvetov liked nature, but he enjoyed it mainly in the Prague gardens in whose neighbourhood he lived. His environment was the city, he never had a car and rarely went outside Prague. He moved around its centre on foot or by tram.

He often rode at night, later evoking the atmosphere of this experience in his surrealist painting “Prague Night Tram”:

A dreamy night vision in the stuck time of the morning, a time beyond space and time, a time when the distinction between dream and reality begins to fade.

Then comes the moment of metamorphosis. Perhaps the cab is still part of the city street, and its passengers can get off at any time, but perhaps they are doomed to become part of it and wander with it forever, through the endless anthracite space, the rain-washed sky.

They enter a new dimension, flying ever onward, movement becoming a constant, points of light brightening all around. A muscular figure, flying through space at the height of his strength, one hand embedded in the hypertrophied tram handle, controlling the motion of the ship, the other holding high the key to the gate of another reality. The figures against it merge with the machine’s construction in hypnotic immobilization and patient surrender, hostages to the impending transformation of time, place and action.

An indifferent profile emerges from space, looking down with motionless indifference on the scene below.

The street lights go out on the city streets, the tram slows down, roaring to a stop. Passengers raise their heads as if trying to remember, staring stiffly with tired eyes. The doors open, releasing them into the raw morning. (A.P-B.)

A Still Life with a Virgin,

1959, oil on canvas, 73 × 54 cm

The Cocoon with the Virgin

During the years of the early and late Surrealist period, Belotsvetov systematically sought out interesting objects to inspire his work. One of the most important places in his collection was occupied by a mannequin he acquired during the liquidation of a hairdressing establishment.

The waxen torso of a woman, whose eerie vividness was enhanced by clear glass eyes and a hairstyle made of real hair, was itself full of surreal symbolism and hidden meanings. One of the most interesting references is to Dali’s “wax doll with a nose of candy” and the figure of Gradiva.

Indeed, the painter called the mannequin a “virgin”, and as an object it was so inspiring to him that it not only gave rise to a large series of still lifes, but appears in his later work in more or less encrypted forms.

The Still Life with a Virgin series was created entirely at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. All of them depict a “virgin” with a classical glass vase, with a view from a studio window in the background.

The simplicity of the recurring theme, however, makes the artist’s boundless imagination stand out all the more. Composition, shapes and colours undergo a constant metamorphosis, juxtapositions and meanings transform with graceful ease. This entire cycle is in fact a long poem, in which each of the images is one of its meaningful metaphors. (A.P-B.)

A Still life with photographer

1959, oil on cardboard, 72,5 × 98 cm

A Still life with photographer (Sudek with Gradiva)

View from the studio window in Újezd. A man with a child is standing in front of the window. They are enveloped in the special magic of the pre-Christmas time. They are each different and yet they have something in common. They are allies of beauty.

The child is looking urgently towards the man and towards us; is he communicating something or is he asking? Perhaps both…

The scene, painted with the confident virtuosity of a great artist and seen through the eyes of a child, has an extraordinarily powerful poetic effect, underlined by the power of magical colour and tiny surreal details.

Needless to say, this man is Josef Sudek, but the painter did, for good measure, write a capital F on his loosely flowing collar – Photographer. He is facing the window, turned away from the viewer, and yet this is one of the best portraits of this brilliant artist. Looking at the characteristic silhouette, his whole figure, his face, animated by the conversation, and his gestures come before my eyes…

The painter and the photographer were long-time friends and gave a lot to each other. That is why this is far from being the only portrait of Josef Sudek in the work of Andrei Belotsvetov, but it is certainly one of the best. (A.P-B.)

Woman with Child

1960s, oil on canvas, 92 × 70 cm

Woman with child

The image of a mother and child, from the first half of the 1960s, bears all the typical features of this period, with its transition from late surrealism to ambiguous experimental-postmodern constructions. The surreal line, so intrinsic to the work that it is almost always present, is also discernible in the complex symbolism of this painting.

The figure of the mother here is diametrically opposed to the loving madonnas we are usually used to seeing in the painter’s paintings. In her haughty and aloof obliviousness, she resembles a barbaric deity rather than a loving woman. Seated in a regal position, she engages in a silent dialogue with two half-hidden figures standing beside her. To her mother’s left we can make out the face of a girl, gazing intently through a rectangular eye, half-obscured by long, pointed lashes. The open, whispering mouth and the long, slender neck suggest, by their peculiar proportions, a possible animal nature.

On the other side of the throne is an entirely different being, rather masculine, with a distinct red arch of the lips, following the line of the mother’s open mouth. A pair of huge eyes, which literally bore into the mother’s face, give this figure the function of a kind of observer. The mother’s motionless face with closed eyes expresses an exalted weariness, but it meets his searching gaze. The robotically machine-like hand of the observer, which is also the mother’s hand, lightly touches the body of the child, standing at the very bottom, under the mother’s breasts, whose prominent red nipples are stylized into the form of staring eyes. The distance between the figures of the child and the mother is expressed both in stylistic difference and composition.

The composition of the figure of the triune Mother impresses with a subtle ambiguity. However, the figure of the child, painted almost realistically, with its pale head curled up to its mother’s breast and its eyes closed, represents an element of poignant human helplessness. This impression is reinforced by the outstretched arms without hands, which we are not sure whether they are hidden in the sleeves or are missing altogether, and by the fact that the child’s face touches the mother’s breast only very gingerly, one could almost say only symbolically. (A.P-B.)

Woman with Child II.version

1960s, oil on canvas, 116 × 80 cm

Woman with child – II.version

The second version of the painting from the same period makes extensive use of the dripping technique, which partly gives the scene a lighter, semi-drawn character. In a sense, it contributes to expressing the shift in meaning that has occurred between the figures. The mother’s attitude is almost unchanged, but her head is no longer turned away indifferently. She looks down with downcast eyes at the child standing between her knees. Her slender torso and delicate hand contrast with the child’s robust body, which no longer looks fragile and helpless; on the contrary, it hugs the mother’s hips with arms stylized in the shape of strong, curved claws in an almost conquering movement. The child’s large head and his mother’s belly merge into a single symbiotic shape. The pair of guides, made up mostly of light lines of cast paint, have become transparent, almost blending into the background of the painting. Only their almost identically stylized heads are distinctive. In their half-decorative, half-anatomical form, they adhere closely to the mother’s head, thus becoming part of it to an even greater extent than in the first version of the painting. (A.P-B.)

Lovers

1970, (reflection of Stanislava Belotsvetova’s poem “Things Are Happening”) oil on cardboard, 49,5 × 70 cm

Things happen

Stuff happens

And your arms wrap around me.

I’m just watching

? I’m looking at

? the extension of torment ?

At the agility and lust

# At the bubble

Just watching

? the all-important naughtiness ?

and the facts will beat you down

? Black is screaming ?

And green grins subtly.

Portrait of Sudek

1953, oil on cardboard, 35 × 25 cm

70s, Sudek,

combined media on paper, 88 × 62 cm

Josef Sudek

Not only did the painter and photographer friends live on the same street, their living arrangements had certain similarities and an unmistakable genius loci. Andrej and Stanislava lived on the first floor of an ancient house with thick walls, at the end of a large courtyard. Behind the row of tenement houses, the noise was a mere echo in the street. The back of the house offered a beautiful view of the vast garden below Petrín, with its ancient stone wall, under the left end of which was the small studio of the sculptor Wichterlová. There was a small garden with several sculptures on the lawn.

Josef Sudek’s home was even stranger, one could almost say surreal. In the courtyard of the inter-block of dignified Art Nouveau tenements and under their strict supervision stood a strange little house that fit its inhabitants – Sudek and his sister – like a tailor-made coat. There was still space left for a charming little garden, from which the artist’s entire series of photographs “The World Outside My Window” is taken.1) The “little house” was reconstructed after Mrs Sudek’s death and turned into the Josef Sudek Museum.

The fact that Andrej’s best friend lived in such close proximity was indeed a great favour of fate for the young family. Sudek helped not only materially, but also as a fatherly advisor and calmer of Andrej’s stormy moods, which he took as a sometimes quite understandable reaction to the hostility and intrigues that were already beginning to swirl around the painter’s person. There is no doubt that emotionally their relationship was somewhat filial and paternal, given their age difference and their fates. However, that would not have been enough in itself. The strength of their friendship lay above all in the extraordinary spiritual kinship, in a kind of kinship of spirit, and in the resulting total respect that each of them felt for the other’s art.

They took supreme pleasure in their conversations together, which they usually expressed through mutual banter and good-natured irony. Both had an enormous propensity for the latter, and I can remember few occasions when I heard either of them speak in all seriousness. They avoided “seriousness” as something beyond and beneath them.

Another thing that closely linked them was music. At Sudek’s Tuesdays the music sounded the finest that a discerning connoisseur could wish for. Even in the otherwise poor household of Andrej and Stanislava, there was no lack of a gramophone, and although their selection of records was not as rich as Sudek’s, it was certainly enough for them to occasionally organize a musical evening, which was of course followed by a lively and long discussion about art…

Although friends saw each other almost daily, it was Sudek’s beautiful habit to leave messages in the mailbox, written on the back of his photographs, which served as a friendly calling card. He liked to take photographs at his parents’ studio and always particularly enjoyed the still lifes that Stanislava arranged for him. He would often ask her on arrival, “So, miss, do you have something new for me to photograph?”

The friendship between these two men never cooled, they always had something to say to each other and was only broken by Sudek’s death in the 1980s. The passing of Josef Sudek was one of the most fatal events in the life of Andrei Belotsvetov. (A.P-B.)

Portrait of Gradiva (Andrea)

1981, Portrait of Gradiva (Andrea), acrylic on cardboard, 35 × 24 cm

Last Portrait of Gradiva

After my parents separated, I often visited my father in his new home, and later my husband and I went to see him together.

After the birth of my first daughter, the situation changed completely. We came to show our newborn granddaughter, but Mrs. Bernard made it clear that she did not want us to visit again.

After some time we tried to come again, and that’s when we found that nothing had changed, that our meetings were definitely over.

However, I often spoke to my father on the phone, and I also went to all his exhibitions.

After many years, a portrait of me came into my hands, painted at a time when we were no longer seeing each other. With a phenomenal painter’s memory, he painted me as he remembered me from our last meeting. (A.P-B.)

The Kid with the Kettle

1982-83, acrylic on sololite, 54 × 80 cm

Child with a teapot

When my friend P.S. brought me this painting he bought for me, I had no idea what a surprise awaited me.

At first, as the dominant feature of the space, I saw a large teapot with steam rising from it. Gradually, other objects and meanings began to materialize. The strangely spiky cloud of steam metamorphosed into the crouched body of a great beast, with its teeth bared and claws extended. It towered menacingly over the teapot, the embodiment of menace.

However, I only understood the full meaning of the scene when, at the bottom of the painting, under the teapot, I could make out the pink, touchingly helpless body of a baby with a pacifier.

I was literally stunned, and the truth appeared before me like a flash: my father was reflecting here on a particularly traumatic experience in our lives that he had apparently never forgiven himself for.

It was when I was less than two years old. My mother had to take care of something quickly and left me in my father’s care for a while. There was no separate kitchen in the studio at Újezd and my parents had to cook on an alcohol stove. My father put water in the kettle for tea and in the meantime went to look at the painted picture. Of course, he forgot the kettle and the babysitter at the relay. I tipped the boiling water over on top of me just as Mum walked in the door.

The burns were unfortunately quite severe, and I took a long time to heal. I was left with a large scar and a compromised immunity as a result of all the vicissitudes. I’ve been sick a lot since then.

Now I was standing in front of a picture that my father had painted many years after the event. It was then that I was confirmed in what I had long ago understood: a true artist does not live his own life fully, he is completely at the mercy of his work. Even such tense and fateful moments are experienced to a large extent through it, and at the same time projected back onto it. (A.P-B.)

Sisyphus

1989, acrylic on sololite, 100 × 120 cm

A barren landscape, with a mountain in the middle, reaching up to the clouds. On it, a human figure is crawling, sweating and bleeding, pushing up a large boulder.

Sisyphus.

It is no coincidence that Andrei Belotsvetov devoted an entire cycle to this theme. He was Sisyphus in the best sense of the word. He wasn’t afraid of the gods or death. He was not afraid of the daily superhuman effort of his work. Every time he reached the top, he could touch the stars, he could touch the divine.

Sisyphus to most people symbolizes a futile effort. Who among us can determine in advance which tasks are futile? The great sisyphos of all time show us the way to achieve the seemingly unattainable. It is they who, in one brief glimpse, open to our eyes a glimpse of the stars, to our parched throats a fountain of knowledge and joy.

Sisyphus Andrei Belotsvetov climbed the mountain for the thousandth time. The boulder trembled and stood. A star rose above his head. He spread his sketchbook on the boulder and began to draw…

Departure

1992, acrylic on sololite, 106 × 79 cm

In the 1980s and 1990s, the painter became increasingly preoccupied with his departure from earthly life. He created two large cycles of paintings, Birds and Departure.

The painting “Departure” (with Magda and the bird) evokes the Ascension of the great Baroque masters in its whole atmosphere: the stiff solemnity of the moment in which time has stopped, the glow of unearthly light that bathes the whole scene, even with the motionless female figure standing still, emerging from the dark shadows.

She is still securely chained to the ground – half woman, half some kind of machine or puppet, symbolizing her earthly destiny. Struck by her encounter with infinity, she gazes fascinated into its depths. Her wonder is escalated to the point of hilarious caricature. A bird perched on her hand gazes towards the radiant freedom.

Everything stops and waits: just a little while longer, then it takes off – and disappears into the blue depths… (A.P-B.)

We Are

1991, acrylic on sololite, 42 × 66 cm

The image “We Are” is thematically related to the “Leaving” series, only it is more encrypted if possible:

The hint of a figure, or rather just a shell of an earthly shape, evokes in its character the female figure-machine from Departure with Magda and the bird.

She, too, finds herself on the border with an unearthly space, from which she exudes a strange strangeness and attraction.

Is she merely meditating while her spirit drifts away with the gliding motion of the curved shell, which is carried away by a strange creature, reminiscent in its purposeful energy of the mealy worm in the 1950s painting, or is the shell already definitively laid to rest in its accustomed position?

Its arm rests on a spatially curved slab – is it perhaps the last contact with earthly roots that are bloodily severed?

The red spot on the arm seems to function as an eye looking through a similarly curved cut-out, a kind of projection window inwards, into the depths of a new reality.

Perhaps it is all a dream, cruel and beautiful at the same time? A dream of freedom and loneliness, of quiet repose and fear of the inevitable?

It doesn’t seem to matter. The philosophical content of the painting is presented with a poetic clarity that is itself an answer. (A.P-B.)